Curtis Tann (1915 – 1991) was an artist, teacher, and a leader of the African American art community in Southern California. He specialized in enamel jewelry.

He was born in Circleville, Ohio on December 4, 1915. His parents both worked. By the time Tann was in elementary school, the family had moved to Cleveland, looking for work in the mills and factories. When the Great Depression started, Tann’s father was fired from his job because he was Black. Consequently, the family suffered hardship.

Initially, Tann learned creative arts from his father, but his father discouraged Tann from becoming an professional artist. Tann’s mother secretly supported his ambition saying “it takes nerve” to become an artist. Eventually, Tann studied at the Cleveland School of Art, and most importantly, at the Karamu House.

Karamu House was a cultural and educational center for Cleveland’s Black community. Tann was introduced to enameling at Karamu House. He studied the Limoges enameling technique under Thomas Usher.

He turned down a scholarship to attend Fisk University so he could earn money to help support his family. Tann made money teaching arts and crafts at the segregated Hiram House Settlement in Cleveland. When Tann tried to introduce integrated programs, his classes were disbanded.

During WWII, Tann served in the U.S. Army. After the war, he moved to Los Angeles with his wife Ethel Mage-Henderson. In Los Angeles, Tann studied at the Chouinard Art Institute. He was a founding member of Eleven Artists Associated (it became the Arts West Association), which helps support Black artists. In Los Angeles, Tann met Betye Brown Saar who became a legendary artist.

Tann and Saar formed the company “Brown and Tann.” They made enameled metalwork and jewelry which they sold at art fairs. Tann and Saar disbanded the company after Saar became interested in printmaking.

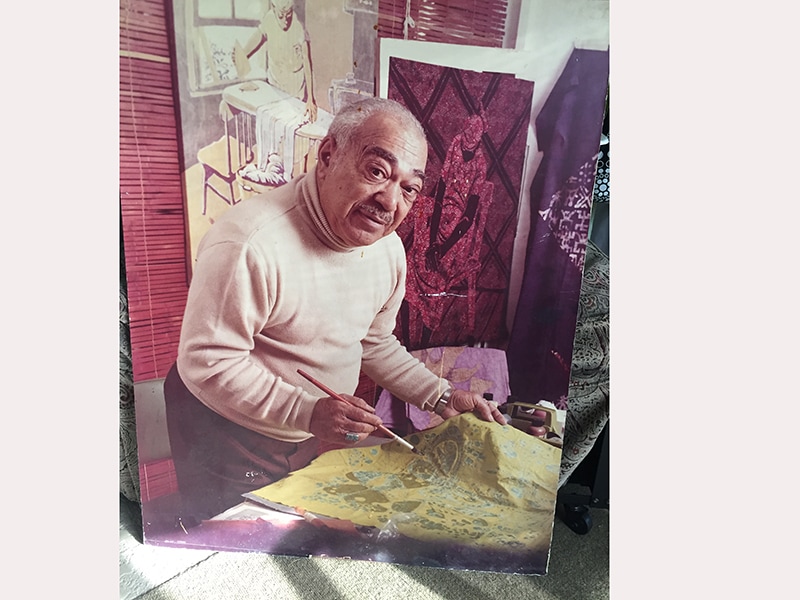

Throughout the 1950s, Tann continued making enamel works on copper. Tann approached enameling like a painter. He said, “I sometimes draw out ideas on paper. I write down colors that I would use. I write down the sequence of certain applications of color and I would also write down the temperatures to gain certain effects…Sometimes I would sift my enamel on the metal and sometimes I would wet-charge it using a brush and water. I would float my color, my enamel into place with water, push it around with a brush and that would give me a painted effect.”

He became a designer and supervisor for the Renoir-Matisse costume jewelry company. Tann’s designs for enamel jewelry used a whimsical style and bright colors. After eleven years at Renoir-Matisse, Tann worked for the jewelry designer Sascha Brastoff for a year.

As a Black man working in a mostly white field with both Renoir-Matisse and Sascha Brastroff, Tann experienced racism. He did not receive royalties or credit for his designs, although the designs were used for years.

As Tann aged, he became more involved with education. In 1967, he became the director of the Simon Rodia Watts Towers Arts Center. He taught classes in enameling, batik, tie dye, and other arts.

Tann died in 1991. His enamel art did not get the recognition it deserved during his lifetime. He left a legacy of education and opportunity for other Black artists.